|

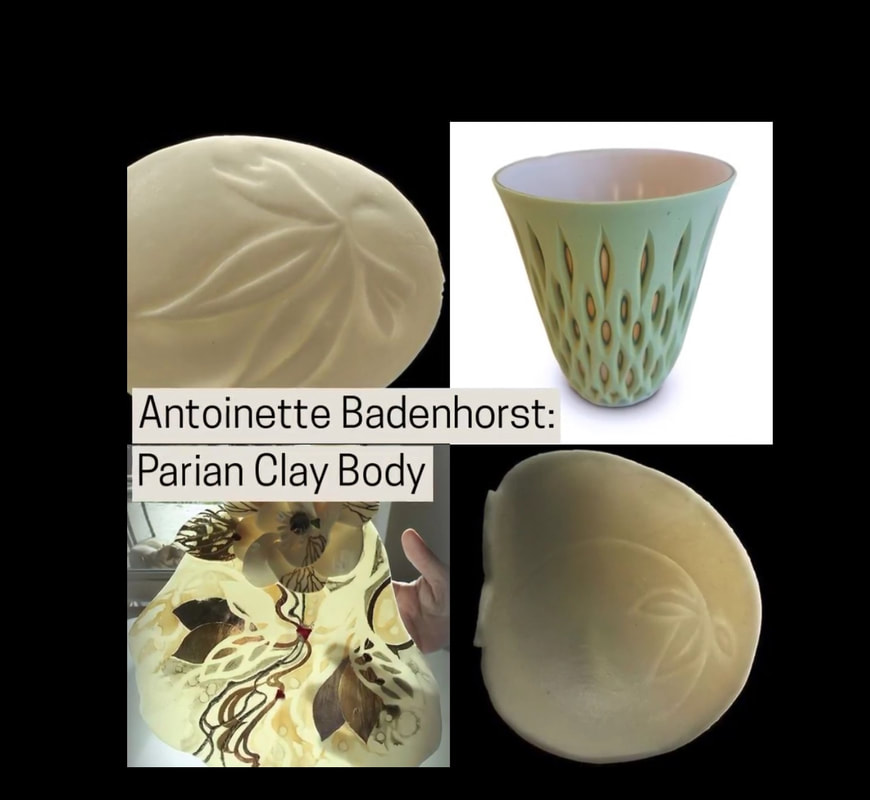

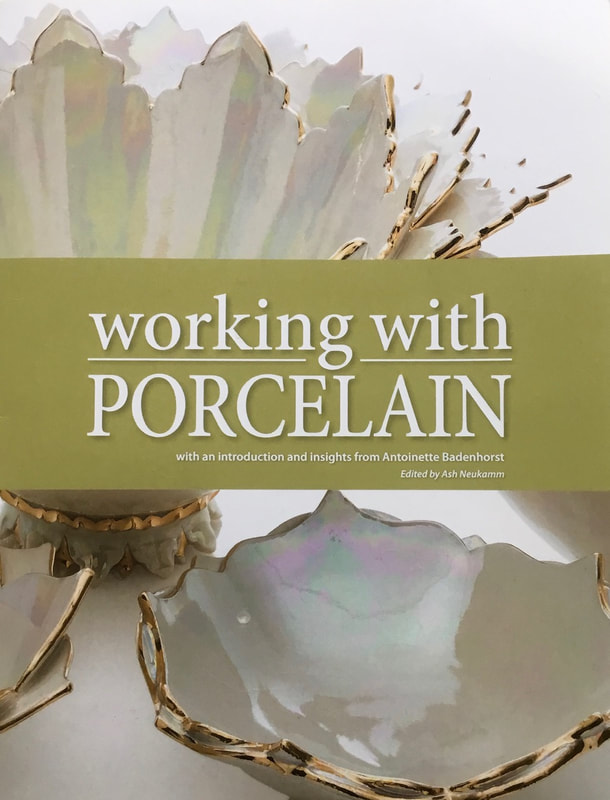

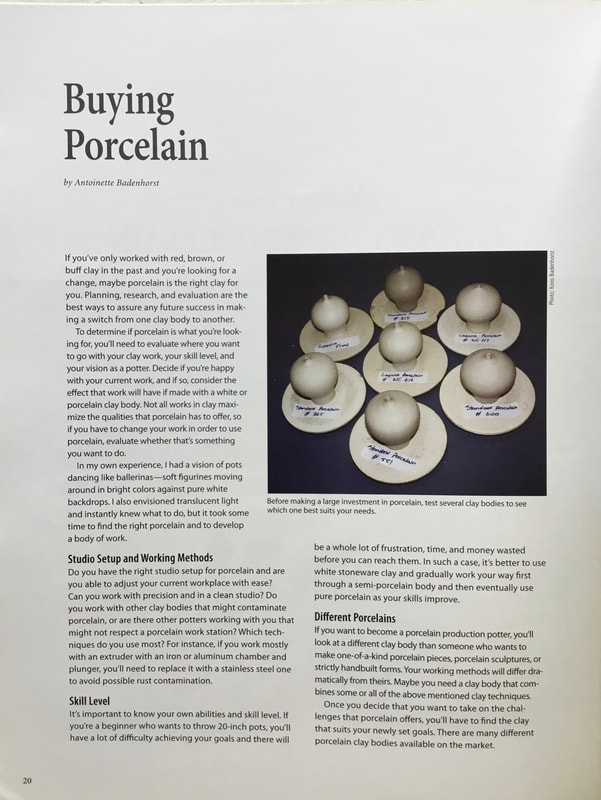

How to create a translucent porcelain clay bodyIn my recent testing of porcelain clay recipes, I wanted to stay as close as possible to the ingredients used in traditional porcelains. My intent was to lower the temperature at which it fires, without sacrificing the properties of vitrification, translucency, and durability. That demanded a closer look at the traditional materials and their chemical makeup.

| ||

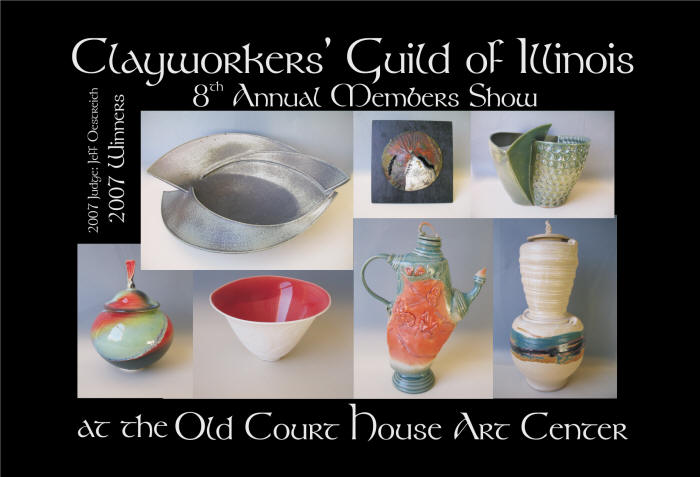

Obtaining translucent porcelainStaying trim was my first published article in the USA. I worked along with, then editor Bill Jones from Pottery Making Illustrated. We published "Staying Trim in 2007.

In working with porcelain, I have expanded the trimming process beyond foot rims to include the entire form, and I now consider trimming to be the most important part of the throwing process. |

| ||

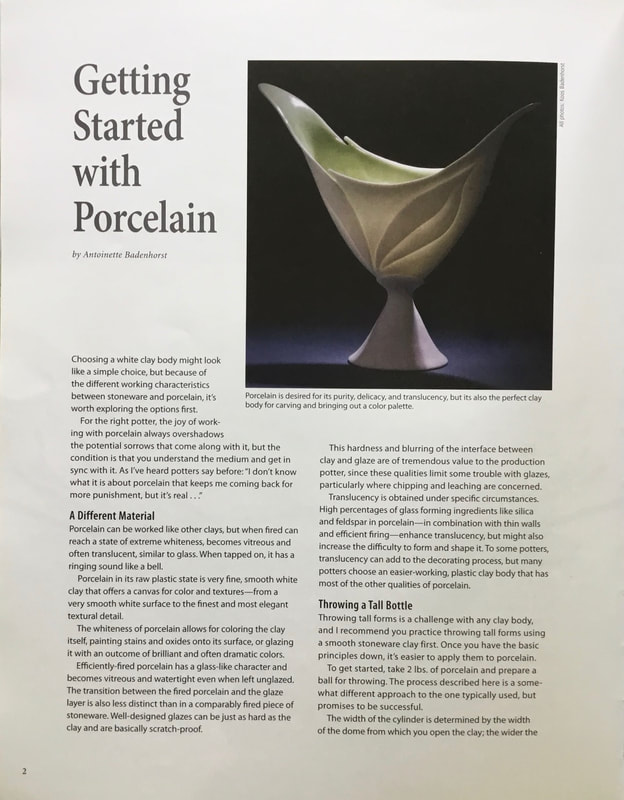

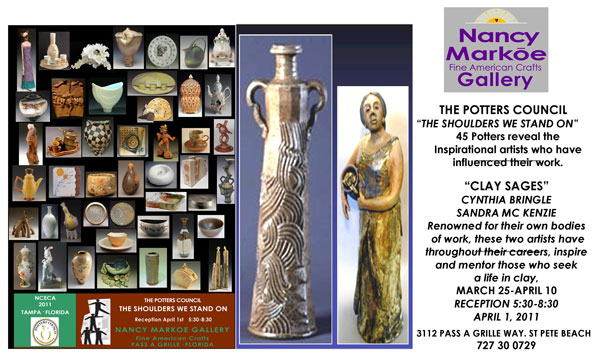

How to begin throwing porcelain on the pottery wheel. Antoinette had her second article published in Pottery Making Illustrated in 2009. Although they published one of Antoinettes' translucent handmade envelopes on the cover of the article, the whole article is about throwing a tall porcelain bottle. See Throwing a Tall bottle.

| |||

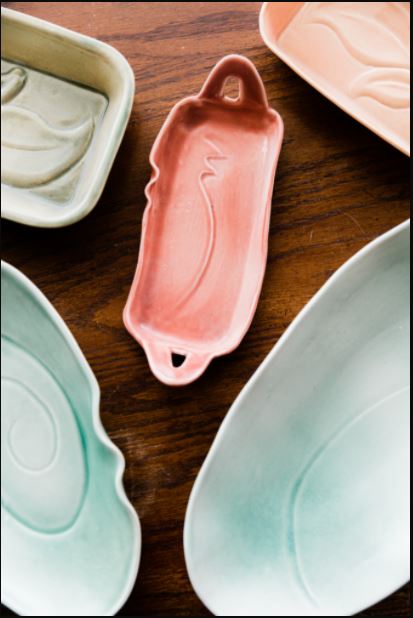

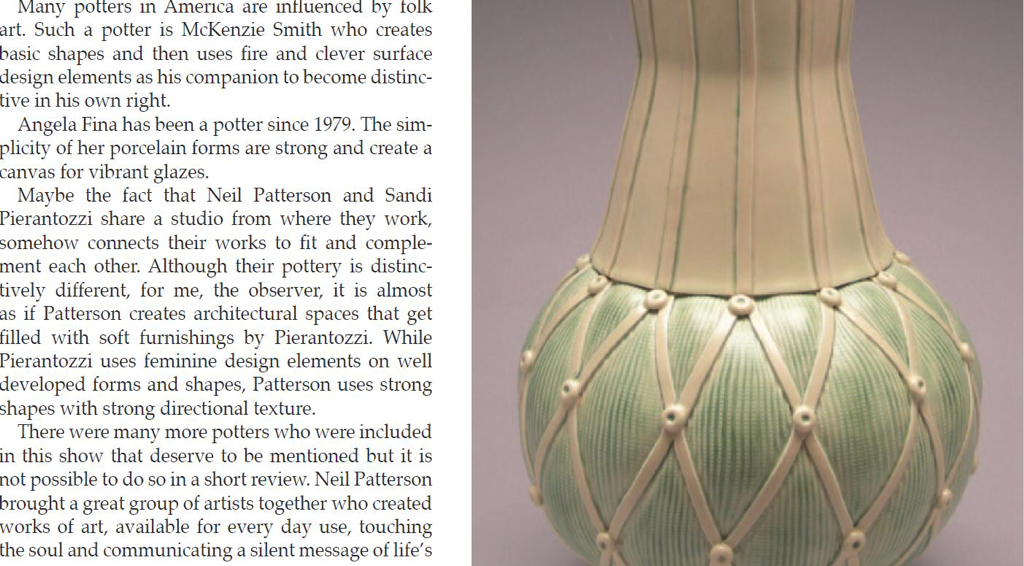

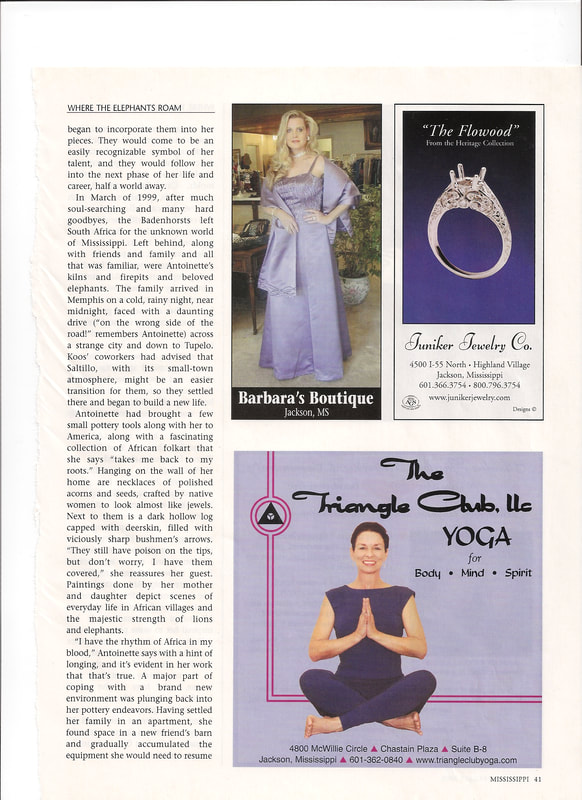

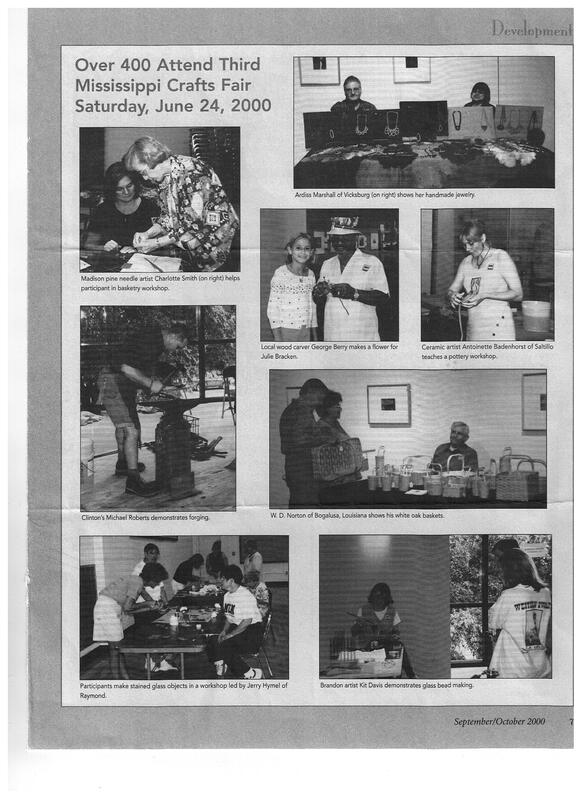

Mississippi Today: A history of artistic tradition

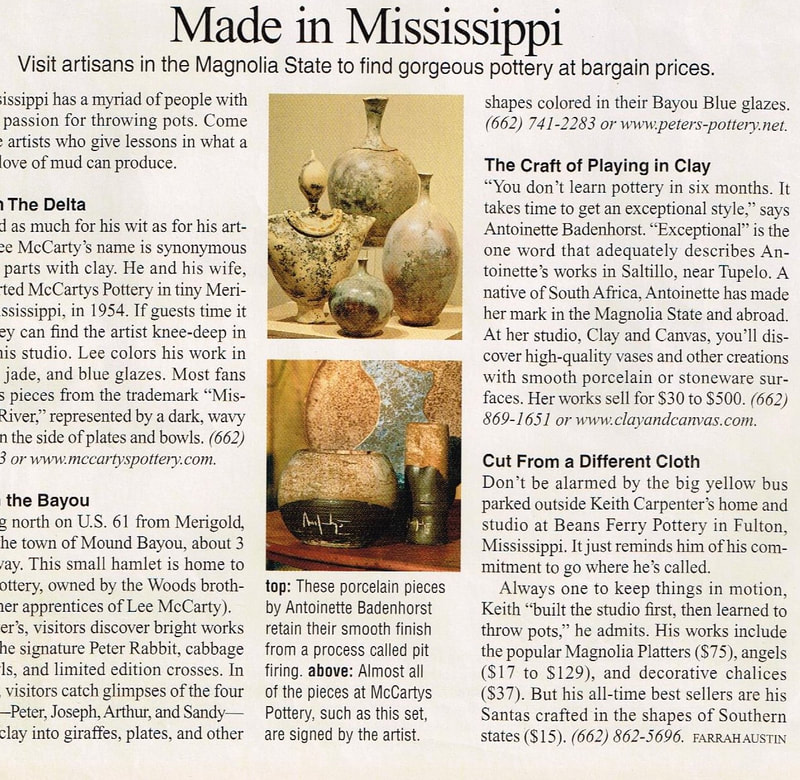

Porcelain by Antoinette featured in Mud and Magnolias

by Kristina Domitrovich

photos by Lindsay Pace

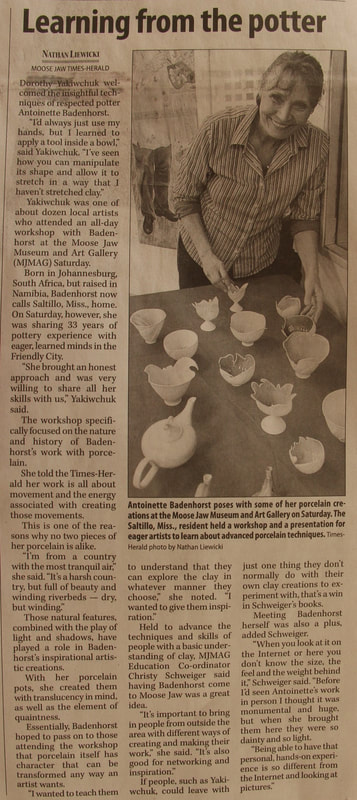

Antoinette Badenhorst is a world-renowned potter and teacher, who reaches students across the globe through her online courses. In a normal year, she travels to teach classes in various countries and holds in-person classes in her studio, though some of that has looked different this past year due to COVID-19. Badenhorst is also a member of the International Academy of Ceramics, a highly prestigious organization that caps its membership at 1,000 artists worldwide.

But like every artist, there was a struggle at the beginning of her career. In fact, as a child, she never even considered herself creative.

Badenhorst was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and was raised in Namibia. Her mom was a painter, but she remembers being shooed away while her mother was working on her pieces: “I think she needed that to concentrate on what she was doing.”

“There was a book of Michelangelo that was sitting on our coffee table in the house,” she remembers. “I don’t know if it was maybe (because it was) sculptures –– I’m not into realistic sculptures –– I’m not into that.”

Badenhorst has a memory of her mother talking on the phone about her. “She was telling somebody else that I’m really creative,” she said.

At first, she thought her mom was surely talking about something she had written, because if Badenhorst liked any art form, it was writing; but instead, it was a craft she made using old Christmas cards.

“It actually ended up on the wall for some reason,” Badenhorst said, somewhat still doubting her younger self.

Not overly interested in visual arts, she enjoyed writing short stories, poems and would later want to become a journalist. But growing up, what she really enjoyed was being outside.

She remembers being outside –– Namibia is mostly made of desert terrain –– entertaining herself.

“I would go out in the country,” she beamed, “And sing loud for myself!”

Badenhorst wouldsit in a rocky area, and she would “make that my little room.” She’d designate certain areas as the kitchen, the bedrooms and so on, and she would make believe and play house. In these little pretend homes, her love for rocks began. She would play with them, examine them and study their texture.

Now when she’s working on a piece, as she’s tracing the lines and grooves in her work, she realizes “it all goes back to those days when I was literally examining rocks.”

But that realization wouldn’t happen for a while, because she didn’t take her first pottery class until later on. Badenhorst attended college and started nursing school, but never finished her studies after she met her now husband and started a family. After their first daughter was born, she walked by an art gallery offering pottery lessons.

“We were dirt poor at the time,” she remembers.

She signed up for the class and paid 20 South African rand for the lessons.

“Less than $2,” Badenhorst said. “And we could barely afford it, but I was too hooked on it.”

Badenhorst took the class for six months, and laughs when she remembers her first, “hideous” pieces. One was a pencil holder that she didn’t properly account for how much the clay would shrink in the kiln; she laughs that it looked more like a snail bowl for serving escargot than anything. The other was a crudely pinched ashtray, though she and her husband didn’t smoke.

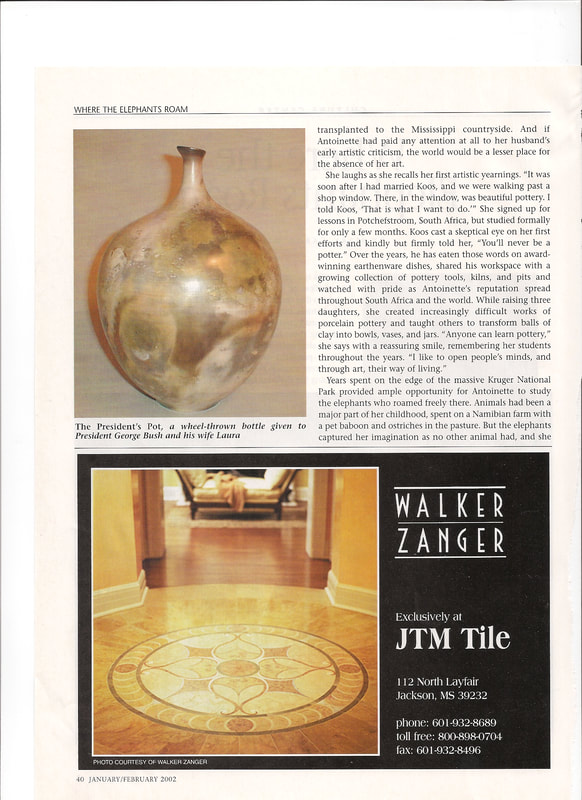

She laughs when she remembers her husband seeing those first pieces: “he said, ‘You’re never going to be a potter.’” Now, he photographs all her pieces and helps with videography for the online classes she teaches.

Badenhorst realizes she’s almost always been a teacher, though she didn’t have an ideal teacher for those first classes.

“The lady (teaching), she was not really interested in teaching me, she was more interested in having the facility so that she could do her own pottery,” she said. Laughing, she adds, “I don’t think I was her favorite student.”

Before she even knew all the ins and outs herself, “very early on” Badenhorst was teaching anyone and everyone who was interested in pottery, “because we lived in a rural area.”

“In the land of the blind,” she says, “I was the one-eyed king.”

Badenhorst believes, this pushed her to stay ahead of the curve and continue to learn as much as she could.

“In those days, there were not a lot of resources available. I remember I had access to one book in the library, which I read and reread and reread again, and it was in English, which is not my first language, so there were many things that kind of fell through the cracks,” she said. “Then later on, I bought myself another book with my very first award money, I bought my first porcelain book, which was the thing that put me on track with what I’m doing here.”

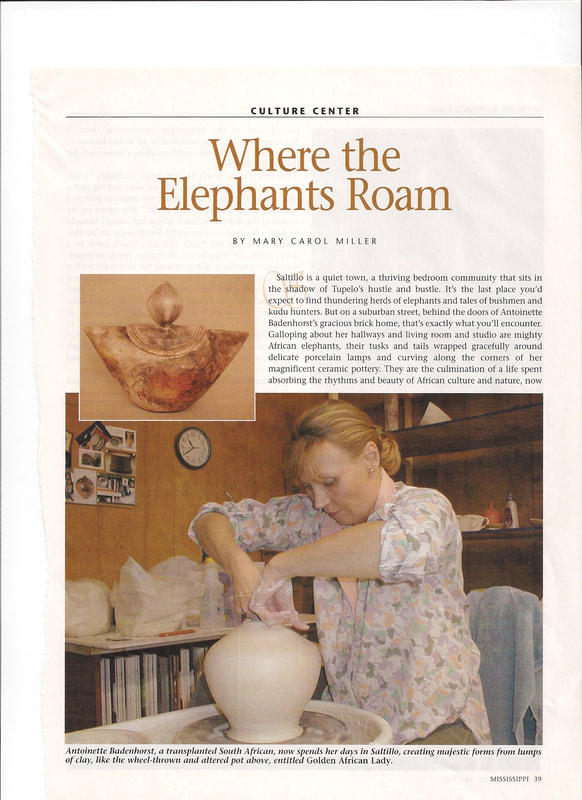

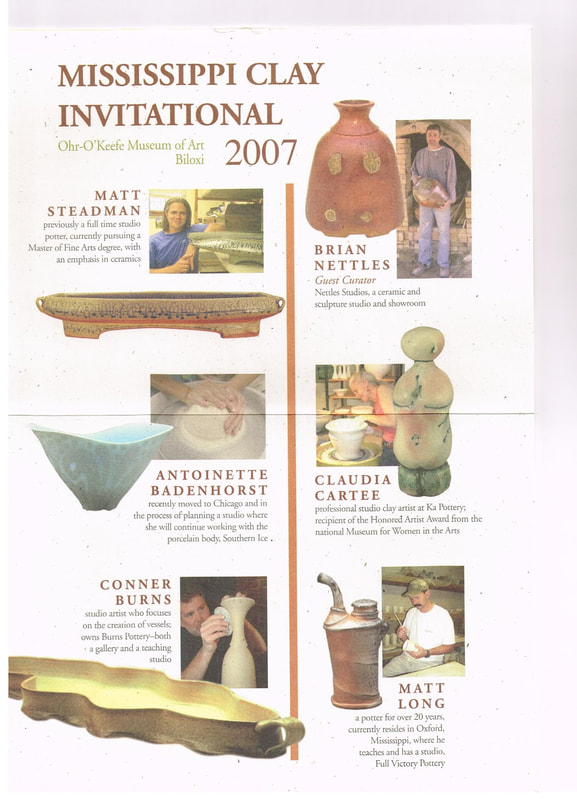

Originally, she started out with ceramics, but before leaving South Africa, she began dabbling in porcelain, which has a higher silica content. In 1999, she and her family moved to the United States, and found themselves in Mississippi for her husband’s work.

When they left, they had 10 boxes of things to bring with them, but the boxes didn’t arrive until about six weeks after they did.

“We literally had nothing,” she said.

With her husband having the work visa, and her not being allowed to earn an income in the U.S. without a green card, she found a potter in Saltillo and made a deal: Badenhorst would work for the potter in the shop, and in return, she would “make myself a few pieces for my kitchen, because we left everything behind in South Africa.”

In no time at all, Badenhorst found herself teaching those there in the studio once again. In November of that same year, she won an award with the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Over the course of five years, she would struggle to get a green card. Her first attempt was denied. After the 9/11 attacks, it set the process back for what would seem like an eternity.

“It was a very insecure period for us,” she recalled.

Eventually, she got her green card and could begin accepting payment for classes and pieces of work, instead of trades she had to use in the limbo to make it as a potter at the time.

She began really focusing on porcelain.

“It’s very hard work. There’s also this kind of love-hate relationship,” she said. “I have to walk away from my work from time to time.”

In 2005, Badenhorst started making translucent pieces. Her pieces look characteristically very delicate and elegant in nature –– and the translucency plays into that. These qualities are why Bardenhorst is so attracted to porcelain.

“I call it a diva. She’s tedious. She’s very unpredictable. But I have a good relationship with her,” she said, grinning.

Badenhorst knows in some ways, porcelain will do what it wants, so she comes to terms with her idea of “perfect imperfection.”

“I use the clay to teach me, to show me what it wants to be,” she says. “I want my work to be smooth. It needs to sit nice and smooth on the table. When you look at it, it needs to be pleasant for the eyes.”

The process of learning what the clay wants to become is a long one, and Badenhorst doesn’t rush it. Oftentimes, she’ll have several pieces covered in plastic in her studio, sometimes sitting there for months as she works on other projects, goes on vacations and comes back to wet the clay and continue grappling with the piece.

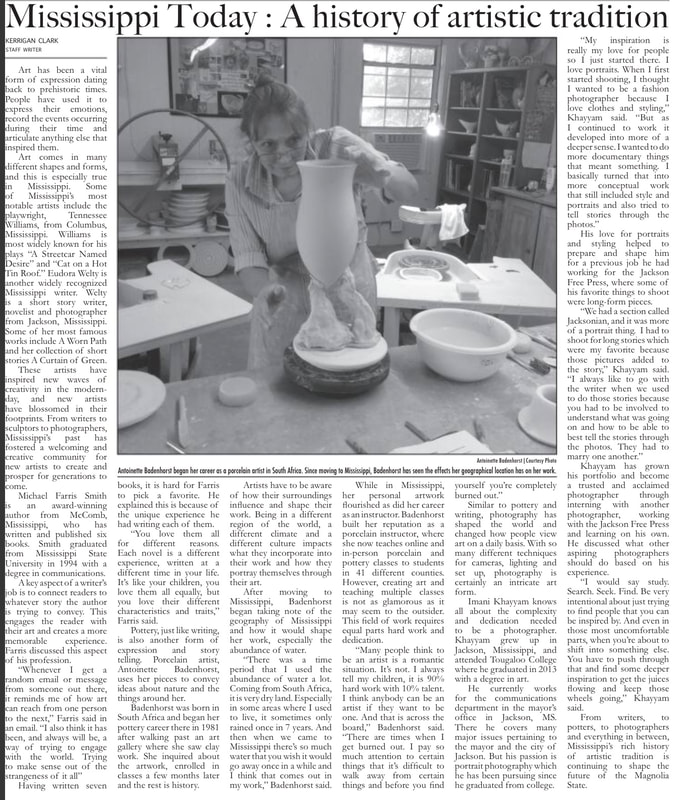

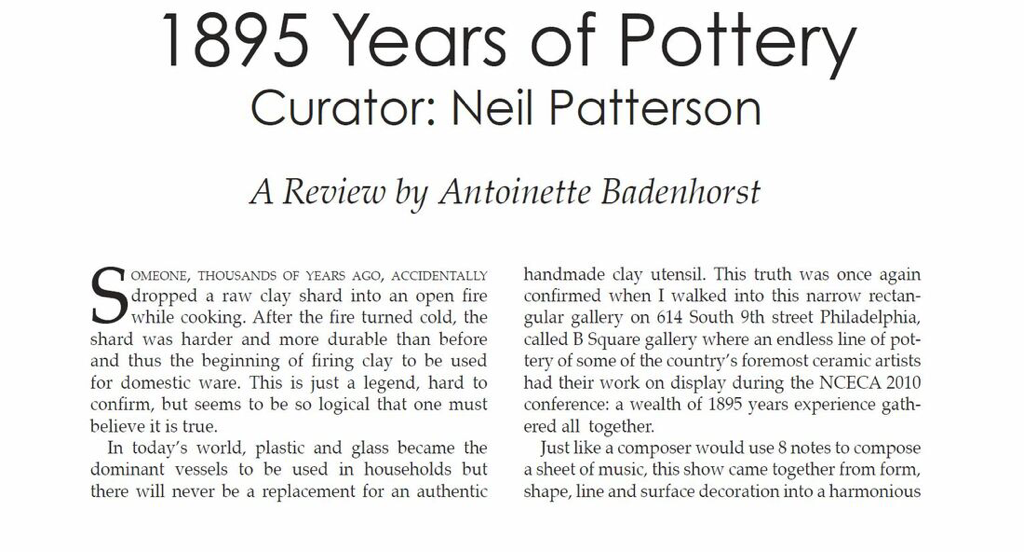

Oftentimes, her decorative pieces like bowls and plates are white on the outside and brightly colored pastels on the inside. When held up to a light, the pieces warmly glow whatever color she has painted the interior.

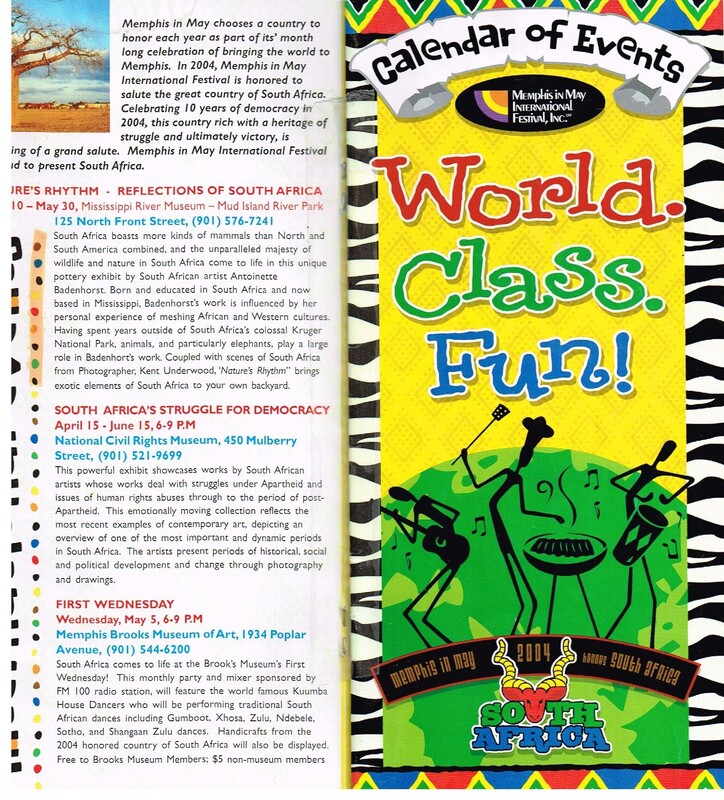

“A lot of what I (am) doing’s referring back to my heritage from South Africa,” she said. “South Africa is considered as a rainbow nation. People are very bright and outspoken with colors.”

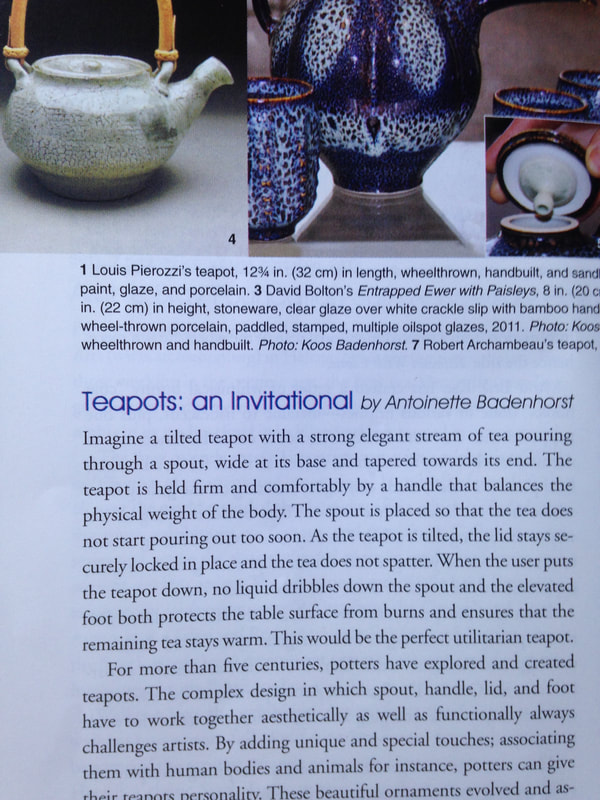

Some things, like her water jugs or tea pots are usually colored on the piece’s exterior. She likes to have fun with the teapots, and will make them by pinching them together.

She says pinching is often viewed as a beginner’s crude method –– picture a small ceramic dish a child would make and give to their mother, or Badenhorst’s first ashtray –– but can be smoothed out and refined with proper practices. She finds the process rather fun. Her teapots are small, smooth and delicate, but her finger’s indentations can be felt from the inside. In a lot of ways, these teapots serve as a personification of Badenhorst’s artistic career and background.

“That juxtaposition between primitive and refined,” she says, drawing the line herself. “First world versus third world.”

Her work shows how she sees the world, too. Not only do the lines and grooves reflect what she sees in nature, but the flow of the leaves reaching out of her pieces show how she sees humanity interacting with itself. Oftentimes, her leaves will grow out from the rest of the piece and touch other leaves. Part of this is because porcelain has glass-like qualities, it needs the structural integrity of leaning on other portions of the work. But she also believes she can see people needing to lean on each other in her leaves. For her, every interaction impacts another person, as seen in her leaves.

She held a bowl with pointier-than-usual leaves jutting from it, some standing on their own. “I was probably in a very sassy mood the day I made that one,” she said giggling.

Things like humanity and nature have a “huge, huge impact” on her and each of her pieces, tracing back to being a little girl, in her make-believe house.

photos by Lindsay Pace

Antoinette Badenhorst is a world-renowned potter and teacher, who reaches students across the globe through her online courses. In a normal year, she travels to teach classes in various countries and holds in-person classes in her studio, though some of that has looked different this past year due to COVID-19. Badenhorst is also a member of the International Academy of Ceramics, a highly prestigious organization that caps its membership at 1,000 artists worldwide.

But like every artist, there was a struggle at the beginning of her career. In fact, as a child, she never even considered herself creative.

Badenhorst was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and was raised in Namibia. Her mom was a painter, but she remembers being shooed away while her mother was working on her pieces: “I think she needed that to concentrate on what she was doing.”

“There was a book of Michelangelo that was sitting on our coffee table in the house,” she remembers. “I don’t know if it was maybe (because it was) sculptures –– I’m not into realistic sculptures –– I’m not into that.”

Badenhorst has a memory of her mother talking on the phone about her. “She was telling somebody else that I’m really creative,” she said.

At first, she thought her mom was surely talking about something she had written, because if Badenhorst liked any art form, it was writing; but instead, it was a craft she made using old Christmas cards.

“It actually ended up on the wall for some reason,” Badenhorst said, somewhat still doubting her younger self.

Not overly interested in visual arts, she enjoyed writing short stories, poems and would later want to become a journalist. But growing up, what she really enjoyed was being outside.

She remembers being outside –– Namibia is mostly made of desert terrain –– entertaining herself.

“I would go out in the country,” she beamed, “And sing loud for myself!”

Badenhorst wouldsit in a rocky area, and she would “make that my little room.” She’d designate certain areas as the kitchen, the bedrooms and so on, and she would make believe and play house. In these little pretend homes, her love for rocks began. She would play with them, examine them and study their texture.

Now when she’s working on a piece, as she’s tracing the lines and grooves in her work, she realizes “it all goes back to those days when I was literally examining rocks.”

But that realization wouldn’t happen for a while, because she didn’t take her first pottery class until later on. Badenhorst attended college and started nursing school, but never finished her studies after she met her now husband and started a family. After their first daughter was born, she walked by an art gallery offering pottery lessons.

“We were dirt poor at the time,” she remembers.

She signed up for the class and paid 20 South African rand for the lessons.

“Less than $2,” Badenhorst said. “And we could barely afford it, but I was too hooked on it.”

Badenhorst took the class for six months, and laughs when she remembers her first, “hideous” pieces. One was a pencil holder that she didn’t properly account for how much the clay would shrink in the kiln; she laughs that it looked more like a snail bowl for serving escargot than anything. The other was a crudely pinched ashtray, though she and her husband didn’t smoke.

She laughs when she remembers her husband seeing those first pieces: “he said, ‘You’re never going to be a potter.’” Now, he photographs all her pieces and helps with videography for the online classes she teaches.

Badenhorst realizes she’s almost always been a teacher, though she didn’t have an ideal teacher for those first classes.

“The lady (teaching), she was not really interested in teaching me, she was more interested in having the facility so that she could do her own pottery,” she said. Laughing, she adds, “I don’t think I was her favorite student.”

Before she even knew all the ins and outs herself, “very early on” Badenhorst was teaching anyone and everyone who was interested in pottery, “because we lived in a rural area.”

“In the land of the blind,” she says, “I was the one-eyed king.”

Badenhorst believes, this pushed her to stay ahead of the curve and continue to learn as much as she could.

“In those days, there were not a lot of resources available. I remember I had access to one book in the library, which I read and reread and reread again, and it was in English, which is not my first language, so there were many things that kind of fell through the cracks,” she said. “Then later on, I bought myself another book with my very first award money, I bought my first porcelain book, which was the thing that put me on track with what I’m doing here.”

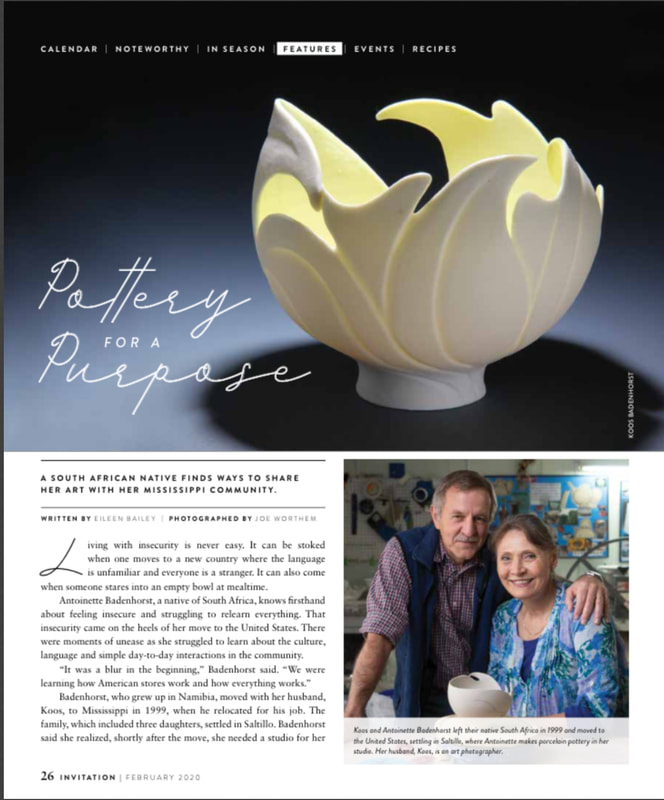

Originally, she started out with ceramics, but before leaving South Africa, she began dabbling in porcelain, which has a higher silica content. In 1999, she and her family moved to the United States, and found themselves in Mississippi for her husband’s work.

When they left, they had 10 boxes of things to bring with them, but the boxes didn’t arrive until about six weeks after they did.

“We literally had nothing,” she said.

With her husband having the work visa, and her not being allowed to earn an income in the U.S. without a green card, she found a potter in Saltillo and made a deal: Badenhorst would work for the potter in the shop, and in return, she would “make myself a few pieces for my kitchen, because we left everything behind in South Africa.”

In no time at all, Badenhorst found herself teaching those there in the studio once again. In November of that same year, she won an award with the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Over the course of five years, she would struggle to get a green card. Her first attempt was denied. After the 9/11 attacks, it set the process back for what would seem like an eternity.

“It was a very insecure period for us,” she recalled.

Eventually, she got her green card and could begin accepting payment for classes and pieces of work, instead of trades she had to use in the limbo to make it as a potter at the time.

She began really focusing on porcelain.

“It’s very hard work. There’s also this kind of love-hate relationship,” she said. “I have to walk away from my work from time to time.”

In 2005, Badenhorst started making translucent pieces. Her pieces look characteristically very delicate and elegant in nature –– and the translucency plays into that. These qualities are why Bardenhorst is so attracted to porcelain.

“I call it a diva. She’s tedious. She’s very unpredictable. But I have a good relationship with her,” she said, grinning.

Badenhorst knows in some ways, porcelain will do what it wants, so she comes to terms with her idea of “perfect imperfection.”

“I use the clay to teach me, to show me what it wants to be,” she says. “I want my work to be smooth. It needs to sit nice and smooth on the table. When you look at it, it needs to be pleasant for the eyes.”

The process of learning what the clay wants to become is a long one, and Badenhorst doesn’t rush it. Oftentimes, she’ll have several pieces covered in plastic in her studio, sometimes sitting there for months as she works on other projects, goes on vacations and comes back to wet the clay and continue grappling with the piece.

Oftentimes, her decorative pieces like bowls and plates are white on the outside and brightly colored pastels on the inside. When held up to a light, the pieces warmly glow whatever color she has painted the interior.

“A lot of what I (am) doing’s referring back to my heritage from South Africa,” she said. “South Africa is considered as a rainbow nation. People are very bright and outspoken with colors.”

Some things, like her water jugs or tea pots are usually colored on the piece’s exterior. She likes to have fun with the teapots, and will make them by pinching them together.

She says pinching is often viewed as a beginner’s crude method –– picture a small ceramic dish a child would make and give to their mother, or Badenhorst’s first ashtray –– but can be smoothed out and refined with proper practices. She finds the process rather fun. Her teapots are small, smooth and delicate, but her finger’s indentations can be felt from the inside. In a lot of ways, these teapots serve as a personification of Badenhorst’s artistic career and background.

“That juxtaposition between primitive and refined,” she says, drawing the line herself. “First world versus third world.”

Her work shows how she sees the world, too. Not only do the lines and grooves reflect what she sees in nature, but the flow of the leaves reaching out of her pieces show how she sees humanity interacting with itself. Oftentimes, her leaves will grow out from the rest of the piece and touch other leaves. Part of this is because porcelain has glass-like qualities, it needs the structural integrity of leaning on other portions of the work. But she also believes she can see people needing to lean on each other in her leaves. For her, every interaction impacts another person, as seen in her leaves.

She held a bowl with pointier-than-usual leaves jutting from it, some standing on their own. “I was probably in a very sassy mood the day I made that one,” she said giggling.

Things like humanity and nature have a “huge, huge impact” on her and each of her pieces, tracing back to being a little girl, in her make-believe house.

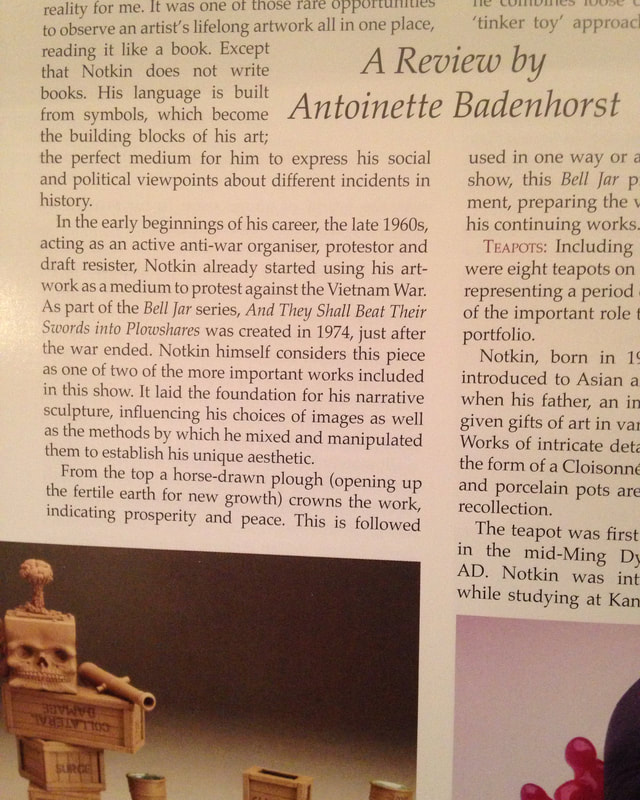

Antoinette's publications

Parian ware

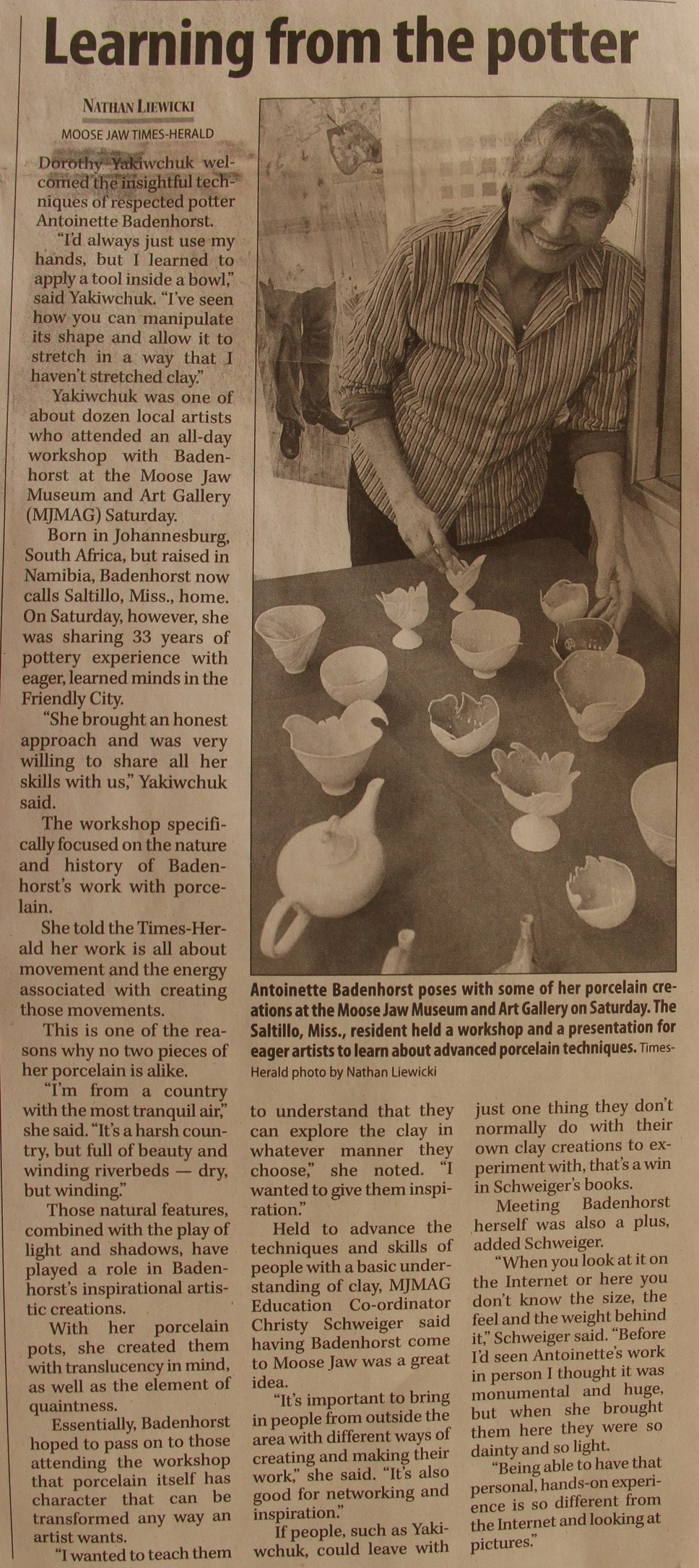

Antoinette wrote many articles over the years, but she is also featured in various communication media, from radio, television and podcasts, to books and magazines. The artist is available to do presentations on various topics related to ceramics, her inspiration and how it is influenced by her spiritual beliefs, her art work and student career choices.

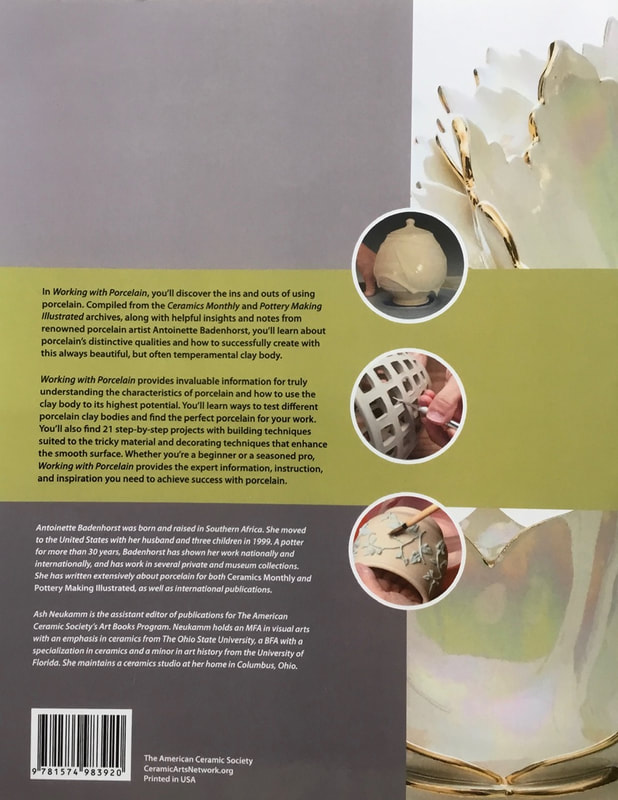

Working with Porcelain by Antoinette badenhorst and Ash NeuKamm

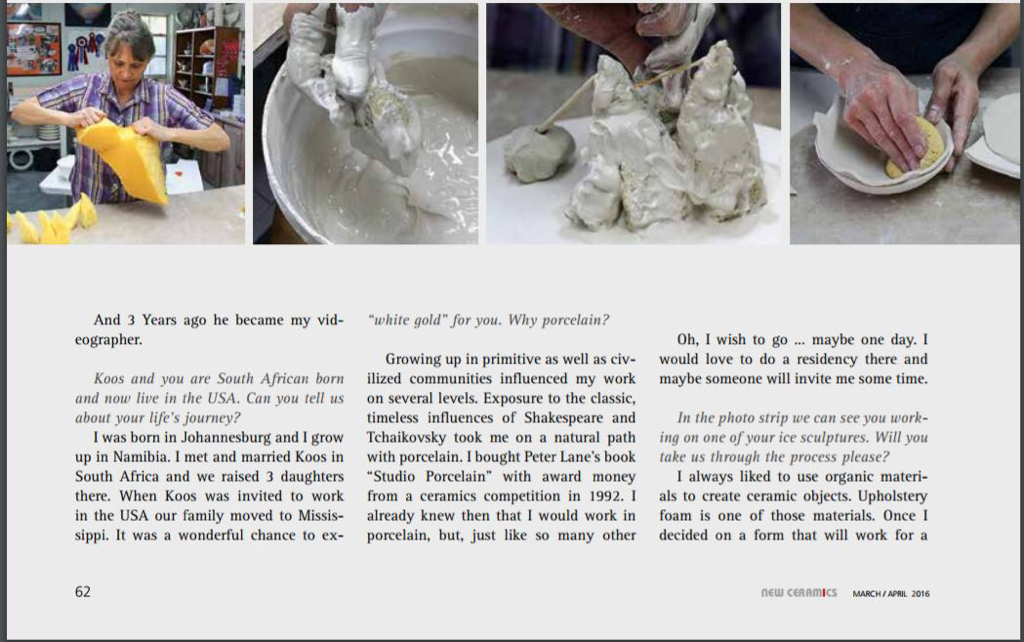

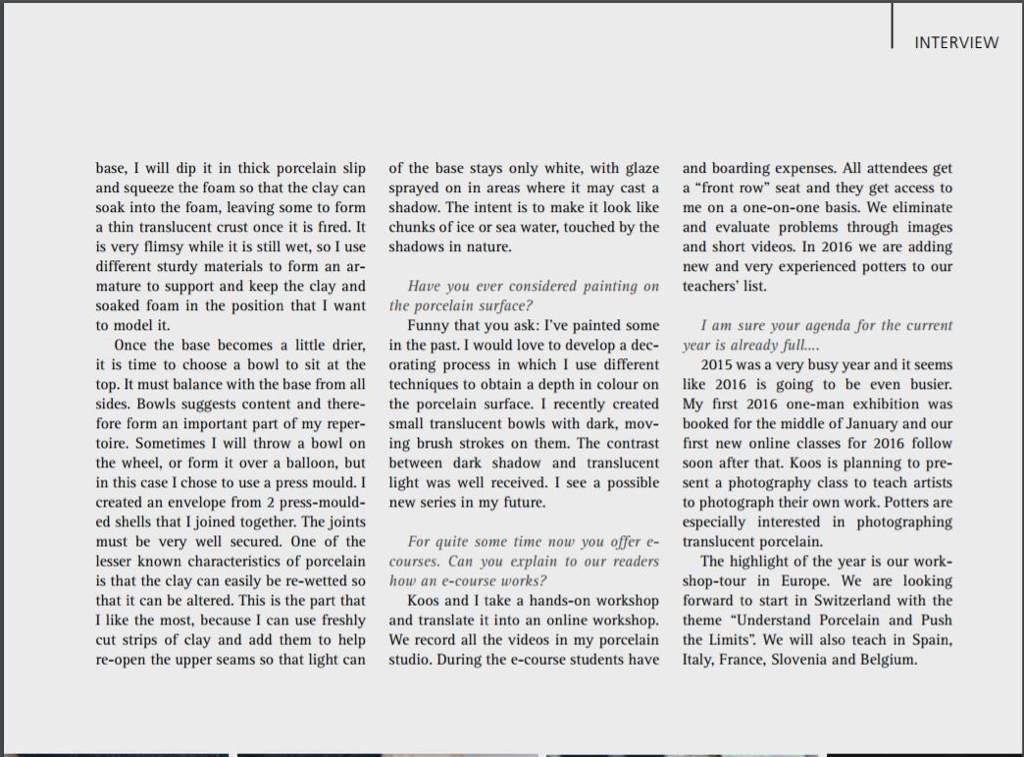

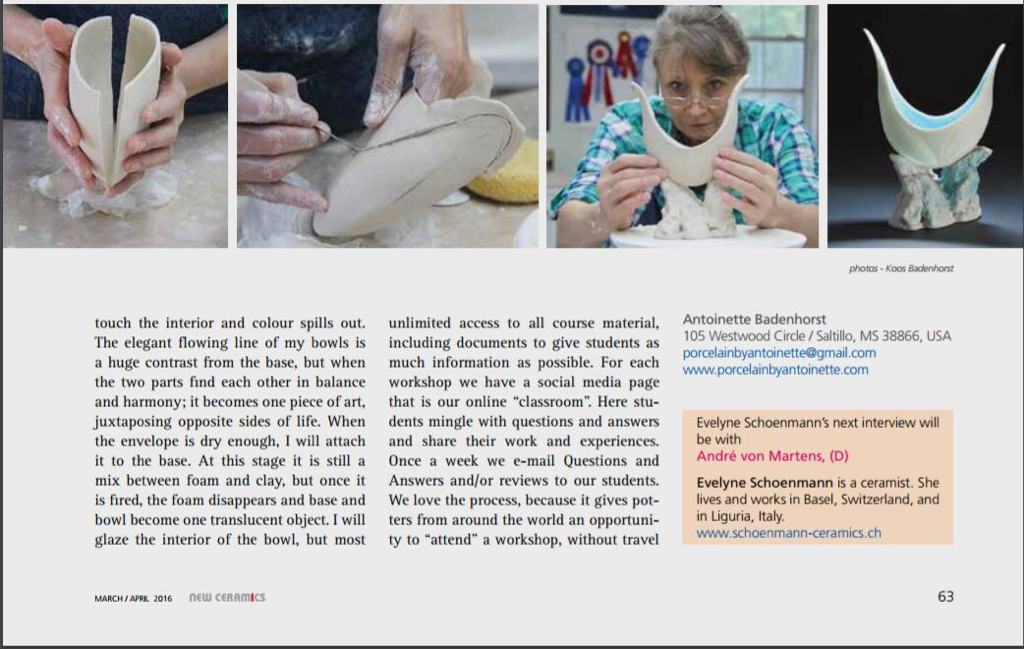

In Studio with Antoinette Badenhorst by Evelyne Schoenmann

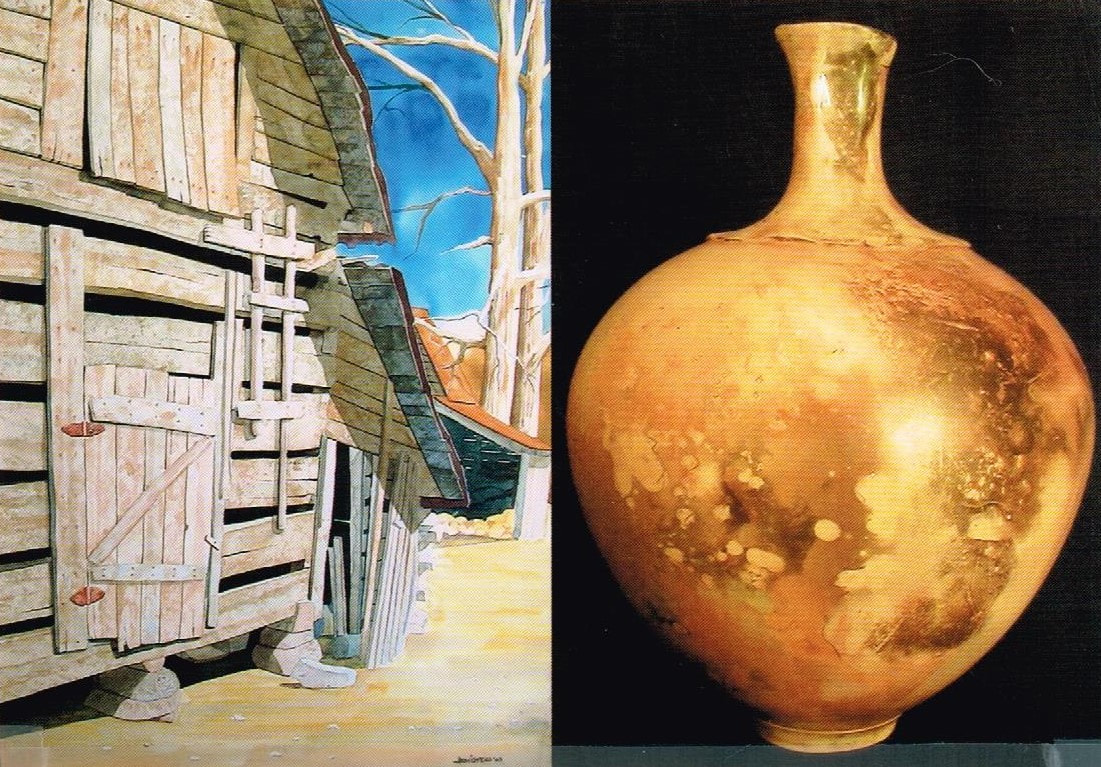

(Art from our stony hills reach Mississippi)

“Kuns uit ons Klipkoppies tref Mississippi”

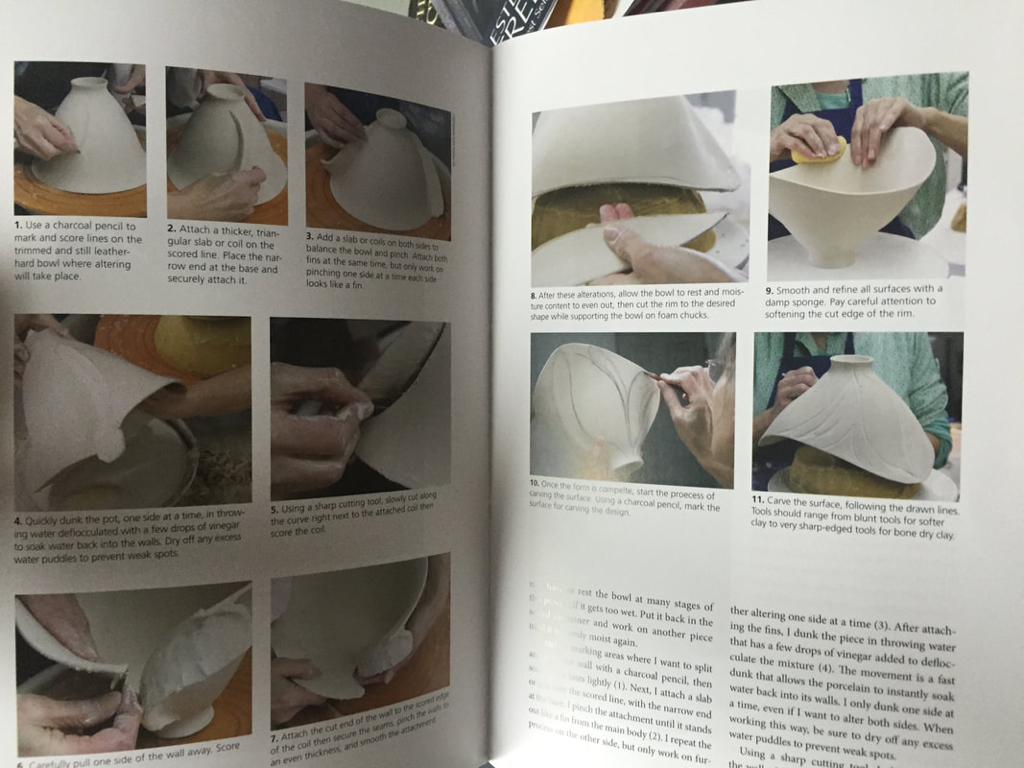

Altered porcelain bowl by Antoinette Badenhorst

“Dancing with the Diva; A porcelain workshops in South Africa with Antoinette Badenhorst”