David is one of the instructors at Teachinart. See his profile here: Click on the image to go to his profile. David is one of the instructors at Teachinart. See his profile here: Click on the image to go to his profile. Kilns suitable for porcelain Now that we established the concept of what porcelain is and how it differs from high firing to low firing porcelains, it is easier to decide what is a suitable kiln to have. The picture is of David Voorhees at his kiln. If you are a truest, believing in only high firing of porcelain, you may also just believe in wood firing, the original firing process in which porcelain was developed in the days that it was still a secret known only to the Chinese. If you are only looking for a strong good and reliable clay experience with the true appearance and qualities of porcelain, any cone firing from cone 6 to 10 should work. Beyond those two firing temperatures, your challenges get bigger.

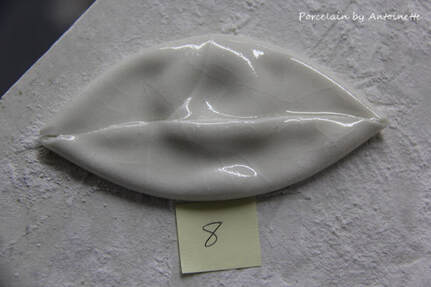

Going below 1220 C (2228 F), can be fired in any pottery kiln, but at this stage the fluxes must also be able to melt at that lower temperature. That is very possible, especially with frits, a factory produced flux that is expensive, but readily available. The problem is that silica and kaolin are both highly refractory, unwilling to melt at such a low temperature. Therefor the heating process must be even, allowing for an even spread of heat and even conversion of silica throughout the mass. Neglecting this process will lead to a surplus of free quartz that will weaken the final ceramics, in this case porcelain. A balance between time and heat, which is possible to manage in a longer cycle of a high firing process, will be more challenging in low firing, which is normally shorter. Therefor an atmosphere of a slow enough firing cycle is needed to allow for and even mingling and integration of silica and alumina with the fluxes at a lower temperature.  One of the clay tests that I did in which the flux was too powerful. One of the clay tests that I did in which the flux was too powerful. The best comparison to the process, is a cake, baked golden brown on the surface but with an unbaked interior. A fine balance of raw materials is needed, complicating the recipe and the chances that one of these materials, may become unreliable when changes in the mining process takes place. To obtain translucency at such a low temperature requires more glass-maker and just a small amount of clay, which forces the clay into a less pliable state. Bentones (macaloid, bentonite vee gum T), may be the only solution to improve workability, but these plasticizers bring its own set of possible problems, a topic that falls out of the scope of this post, but that may be discussed in future. It may be a good time to refer back to soft paste porcelain Chicago images, which is traditionally not as strong as hard paste porcelain. Anyone interested in working with clay should choose the medium and firing requirements first and then decide on which kiln to buy. Porcelain, in general do have its own requirements for firing, whether it is a high firing or low firing porcelain. I describe some of these requirements in the blogpost "Slow firing of porcelain in a pottery kiln". It often requires down-firing. Frank and Janet Hamer described it in “The Potter’s Dictionary of Materials and Techniques” as “a thick body-glaze layer”. Due to its glaze-like nature, described in by as “a thick body-glaze layer”. Due to the fact that the clay and glaze matures at the same time, it builds a very strong bond by the clay body compressing the glaze. A simple explanation is that the clay prevents the glaze from stretching too much, prevent it to craze, thus the stronger bond. Too much compression will cause shivering.

Porcelain is considered a dense ceramic material, as it contains 10% +cristobalite from silica present in the clay. Body and glaze contract together during the cooling, compressing it into a strong bond. If the critical cooling periods around 573 C (1063 F) and again around 226 C (439 F) when free quartz and cristobalite needs to contract in concert with each other at the same slow rate, is not slow enough, the tension build up will weaken and break the body in two, many times long, sometimes even weeks after the work is cooled.

1 Comment

|

Blog

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed